Abstract

The intricate process of wound healing involves the regeneration of tissue through a series of molecular cellular events that follow the onset of tissue injury and ultimately restore the damaged tissue. comprises of hemostasis that proliferates. The progressive processes of inflammation and remolding are brought about by the interaction of soluble mediators such as parenchymal and blood cells. The healing process of wounds is affected in all phases, even though the elderly can heal most wounds more slowly. Topical therapies that target specific biochemical and molecular pathways show promise for enhancing and, in some cases, normalizing the healing process and the use of anti-inflammatory medications. Skin wounds are typically divided into acute and chronic categories. Age-related variations in wound healing as well as better biology and clinical understanding of the processes behind acute and chronic wound infection repair have been well-documented.

Keywords

Wound Healing, Acute Wound, Chronic Wound, Inflammation.

Introduction

By definition, chronic wounds are those that have not healed through the typical phases and have instead descended into a pathologic inflammatory state (1). These wounds are characterized by chronicity and frequent relapses, and they cause significant disability. If the factors preventing wound healing are properly identified and managed, these wounds will frequently heal quickly. According to available data, recombinant growth factor therapy might offer an extra boost to the healing of specific kinds of chronic wounds. It contains a complex process that is governed by Following a skin injury, the exposed sub-endothelium, collagen, and tissue factor will undergo overlapping phases, including the haemostasias/inflammation phase, proliferation phase, and remodeling phase (2). Here, we go over what is currently known about skin repair and show how impaired cells behave to reduce pain. Pathology of chronic wound healing. Chronic wounds are often plagued by infection, which frequently results in nonhealing and substantial patient morbidity and mortality (3). Wounds with poor healing, such as chronic and delayed acute wounds, typically have not advanced through the healing phases. Such wounds often experience a delayed, incomplete, or disorganized healing process, which leads to a state of pathologic inflammation (4). The healthcare system is heavily burdened by impaired wound healing. Controlling burns Due to the severity of the injury, wounds are also very difficult. Wound care has been practiced for thousands of years; the earliest treatments involved covering the wound with cloth and leaves and using natural ointments to keep the wound closed, lessen pain, and avoid infection. It has been demonstrated that some of these strategies are insufficient to induce healing in chronic wounds, even though they are still used to keep the wound open. Furthermore, scaffolds can be functionalized with a variety of substances to improve cellular reactions and accelerate the healing process of wounds (5).

Cellular Aspects of Wound Repair:

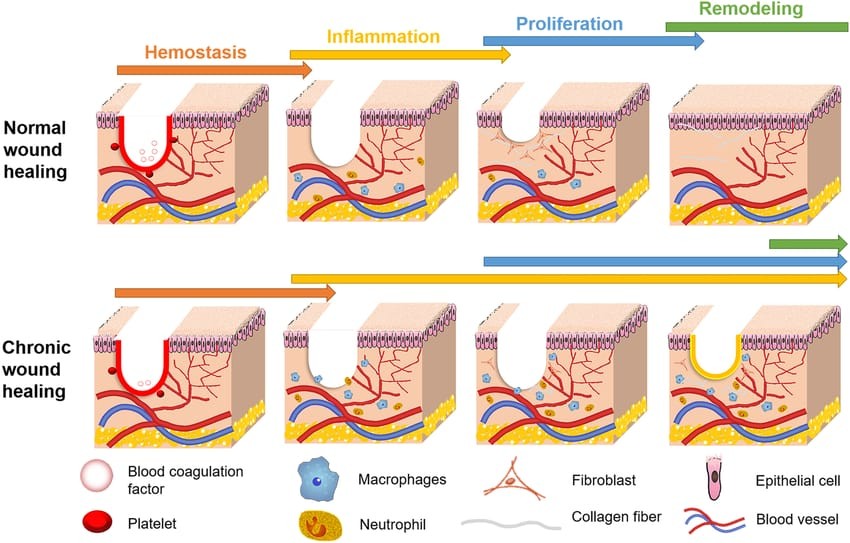

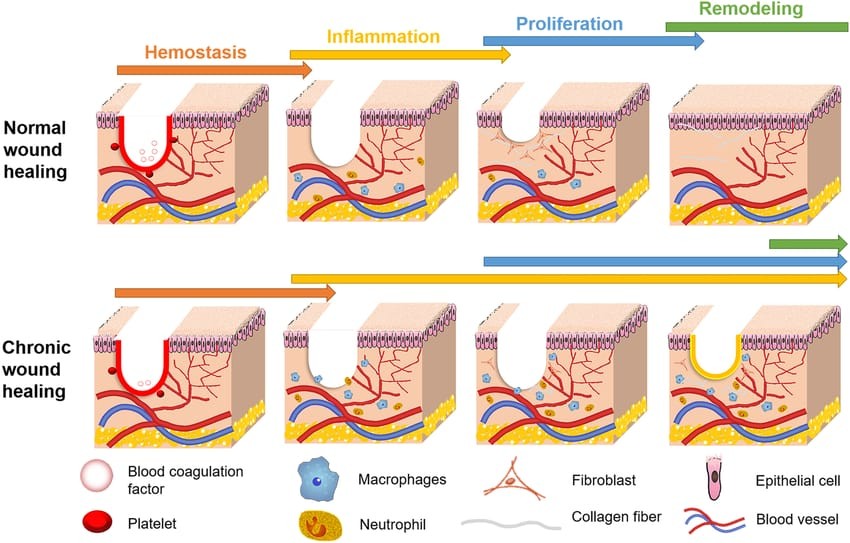

our skin is specialized to interface with the external environment and provides a variety of important hemostasis functions, from regulating thermostability to sensing extrinsic stimuli. The skin has also evolved efficient and rapid mechanism to close breaches to its barrier in a process collectively known as healing response wound repair is Classically Simplified into four main phases hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and dermal remodeling.

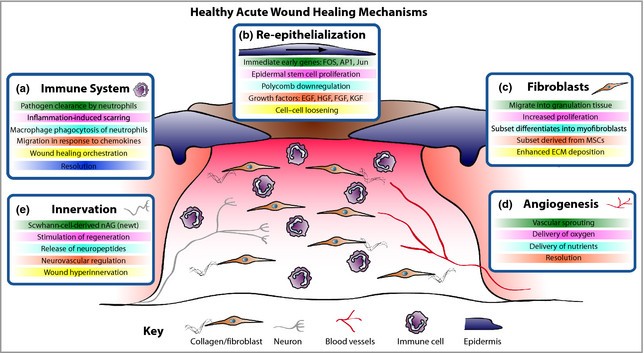

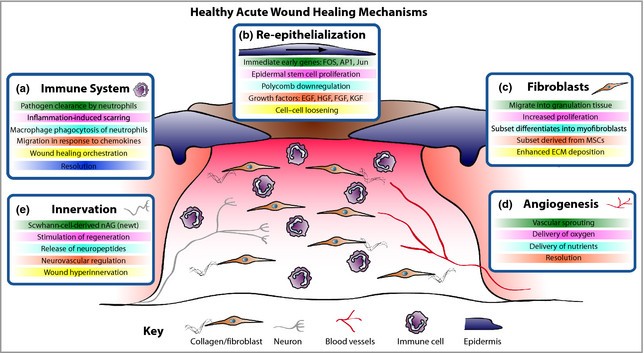

Figure 1: The stages of wound repair and their major Cellular component

Hemostasis:

Damaged arterial vessels quickly constrict due to the concentration of smooth muscle in the circular lager of the vessel wall, which is mediated by rising cytoplasmic calcium levels (6). This is the body's immediate reaction to prevent exsanguination and promote hemostasis upon injury, resulting in rapid contact and the formation of a blood clot that prevents exsanguination (7).

Inflammation:

Tissue damage triggers a cellular and vascular reaction that removes foreign objects and devitalized tissue from the wound and prepares it for tissue regeneration and repair. There are two parts to this inflammatory reaction. In response to particular chemotactic substances produced in the wound, there is a vasomotor Vaso permeability response that causes localized vasodilation, enhanced capillary permeability, and a leukocyte infiltration (8).

Proliferation:

Not much research has been done on how arginine affects cell proliferation. For a wide range of cells, including lymphocytes, to grow as best they can in vitro, arginine is necessary. The production of polyamines, which come from the metabolism of arginine, is crucial to cell proliferation. When added in greater concentrations, polyamines can be harmful and growth-inhibiting in both vitro and vivo settings (9).

Remodeling:

Remodeling (Coming of Age)

Duration: After an injury, weeks to years. The newly created tissue develops and gets stronger. Along tension. lines, collagen fibers undergo remodeling and realignment. The more stable the tissue, the less vascularization there is. Depending on the extent and size of the wound, this stage could last anywhere from a few months to several years (10).

Mechanism of Acute wound healing:

Following skin damage, wound healing entails a complicated interaction between numerous skin cellular actors, chiefly keratinocytes, fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, recruited immune cells, and the extracellular matrix that surrounds them. Restoring a functional epidermal barrier is very effective in healthy people, but repairing the deeper dermal layer is less successful and causes scarring along with a significant loss of the original tissue's structure and function. An ulcerative skin defect (chronic wound) or excessive scar tissue formation (hypertrophic scar or keloid) are the two main results when the usual repair process goes astray. To help with wound contraction, some fibroblasts undergo myofibroblast differentiation. (d) Angiogenesis produces new blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to the wound bed. € Although innervation and wound healing rates are positively correlated, hyperinnervation following wound closure may be a factor in neuropathic pain. HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor. Since tissue repair occurs in all multicellular organisms, we assume that many conserved mechanisms can be examined in models that are easier to conduct experiments on than humans and then applied to the clinic for possible therapeutic benefit. Pig models of wound healing were first used to study repair mechanisms due to their resemblance to human skin.1 They are still frequently used as models for preclinical testing of possible treatments. However, rodents are now the most common models for examining the basic cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying tissue repair due to cost concerns and genetic opportunities (11).

Figure 2: Mechanism of Normal Wound Healing

Mechanism of Chronic Wound Healing:

The intricate interaction of biological processes involved in chronic wound healing can be interfered with, resulting in wounds that take a long time to heal. Typical chronic wound healing mechanisms include:

1. Inflammation: Prolonged inflammation is a common feature of chronic wounds. This may be brought on by foreign objects, recurring infections, or underlying diseases like diabetes. The inflammatory response can be sustained by inflammatory cytokines like TNF-a and IL-1, which can stop the healing process from progressing to the subsequent stages.

2. Cellular Dysfunction: In chronic wounds, important cell types that aid in wound healing, such as fibroblasts and keratinocytes, may stop functioning properly. Fibroblasts might not move or effectively multiply, resulting in insufficient production of extracellular matrix (ECM) (12).

3. Matrix Remodeling: An imbalance in ECM remodeling is frequently seen in chronic wounds. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which break down ECM components and prevent appropriate wound closure and repair, may be overproduced.

4. Reduced Angiogenesis: Angiogenesis, which is essential for supplying the oxygen and nutrients required for healing, may be compromised in chronic wounds. It is possible for certain factors, like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to be downregulated.

5. Hypoxia: The hypoxic environment in which chronic wounds often reside can hinder their ability to heal. Numerous cellular processes, such as collagen synthesis and cell division, depend on oxygen (13).

6. Biofilm Formation: In chronic wounds, persistent bacterial biofilms can develop, resulting in a persistent infection that makes healing even more difficult. Biofilms shield microorganisms from the antibiotics and the immune system.

7. Immune System Dysregulation: Modified macrophage polarization (from M1 to M2 phenotype) can result in a dysfunctional immune response in chronic wounds, which hinders healing. M2 phenotypes encourage tissue repair, whereas M1 phenotypes tend to be pro- inflammatory.

8. Systemic Factors: By influencing both local and systemic reactions, comorbid conditions like diabetes, obesity, and vascular disease can further hinder wound healing (14).

Figure 3: Mechanism of Chronic Wound Healing

Wound Healing in The Fetus and Adult:

It is clear that age affects one’s capacity to heal wounds without excessive wound healing. The greater the likelihood of excessive wound healing, the older one gets. The regeneration of normal dermal architecture, including the restoration of dermal appendages and neuro vasculature, is a characteristic of fetal wound healing. The fetal skin’s wound healing process also involves a unique GF pro-file, a lowered inflammatory response with an anti- inflammatory cytokine profile, less biomechanical stress, an extracellular matrix rich in type III collagen and hyaluronic acid, and a possible role for stem cells. In contrast to fetal skin, adult skin is more likely to create scars. At least four different methods exist to demonstrate how the skin of a fetus and an adult heals differently from one another. An inflammatory response accompanied by neutrophil and macrophage migration characterizes the early stages of adult healing; in a fetus, however, inflammation is not visible. Research indicates that the fetal wound has a lower concentration of inflammatory cells compared to the adult wound. Research has revealed that a number of cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-8, are much higher during the adult healing process than during the prenatal healing process. On the other hand, IL-10 levels are higher during fetal healing than during adult healing. The adult wound has lower quantities of TGF-B3, but larger concentrations of TGF-B1 and TGF-B2. There is a notable differential in the ECM composition between wounds in fetuses and adults. In the fetal wound, there is an increased ratio of type III to type I collagen and a higher rate of fibroblast production of extracellular matrix (ECM). Hyaluronic acid content in the extracellular matrix (ECM) is likewise higher in fetal wounds than in adult wounds. Only mature wounds contain myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts in the adult wound become increasingly noticeable as the wound’s mechanical strain rises. In contrast, the fetal wound has either none or extremely few myofibroblasts. Thus, more research into the basic mechanisms behind neonatal wound healing will provide possible solutions to reduce the amount of scarring (15).

Factors of Wound Healing:

- Growth Factors: These are proteins that promote the division, growth, and proliferation of cells. Important growth factors for the healing of wounds include (16).

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): During the healing process, the ECM is essential for cellular signaling and for giving tissues structural stability (17).

- Oxygen: Because it promotes cellular metabolism and is essential for the creation of collagen, adequate oxygen levels are critical for healing (18).

- Inflammation: To remove germs and debris, the right amount of inflammation is required, but it must be carefully controlled to prevent chronic wounds (19).

- Nutritional Status: For the best possible healing, nutrients including zinc, protein, vitamin C, and arginine are necessary (20).

- Age: Growing older impairs tissues’ ability to regenerate and may cause a delay in the healing of wounds (21).

- Systemic Conditions: The healing process might be hampered by diabetes, vascular disorders, and other systemic conditions (22).

- Infection: The existence of an infection can causes problems and considerably slow down the healing process (23).

Topical Medicine for Wound Healing:

- Hydrocolloid Dressings: These dressings shield the wound from impurities and create a moist environment that encourages healing. They work particularly well for pressure ulcers, minor burns, and abrasions.

- Silver Sulfadiazine: Burn injuries are frequently treated with this antimicrobial cream. It can speed up the healing process and help avoid bacterial infections (24).

- Honey: Antibacterial qualities of medical-grade honey, especially Manuka honey, can aid in the healing of chronic wounds. It can lessen inflammation and keeps the wound environment moist.

- Growth Factor Products: Growth factor- containing topical. treatments, like platelet- derived growth factor (PDGF), can hasten the healing of chronic wounds (25).

- Antiseptics: Although they must be used carefully to prevent cytotoxicity, solutions such as silver ion dressings or iodine-based products (such as povidone-iodine) can be used to prevent infection.

- Chitosan: Because of its antibacterial and biocompatible qualities, this biopolymer has been demonstrated to aid in wound healing (26).

Medication and Drugs:

Numerous treatments and pharmaceuticals can have an impact on the complicated process of wound healing. These are some important drug classes that are frequently used to enhance wound healing, along with them.

1.Antiseptics used topically: Frequently applied to burn injuries, silver sulfadiazine has broad-spectrum antibacterial properties.

Honey: renowned for its antimicrobial qualities and capacity to aid in the healing process (27).

2. Elements of Growth: Recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor, or rhPDGF, stimulates angiogenesis and cell division. The proliferation of epithelial cells is stimulated by epidermal growth factor (EGF) (28).

3. NSAIDs, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Although their primary function is to alleviate pain, they have the ability to regulate inflammation and may indirectly aid in the healing process (29).

4. Antibiotics used topically: Mupirocin and Bacitracin: Used to stop minor wounds and abrasions from getting infected (30).

5. Antibiotics for the system: Antibiotics such as cephalexin or ciprofloxacin may be used to treat infected wounds (31).

6. Pain Control: Pain management is essential for patient comfort and movement during the healing process, and opioids and local anesthetics can aid (32).

7. Supplemental Nutrition: Collagen synthesis and general healing depend on zinc and vitamin C (33).

8. Cellular Treatments: Mesenchymal stem cells are used to promote tissue regeneration in long-term wounds (34).

CONCLUSION

Hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling are some of the stages of the intricate biological process that is wound healing. In order to restore tissue integrity and function, each stage is essential. In summary, appropriate evaluation and management of the wound environment- including elements like infection prevention, moisture balance, and sufficient nutrition-are necessary for successful wound healing. Knowing the fundamental processes of healing can help guide treatment plans and enhance results.

REFERENCE

- Nathan B. Menke. MD (a,b) , kevin R word MD (a,b) Tarynm M. Written, PhD (c,d) , Danail G. Bonchev, PhD(c,d) , Robert F Diegelmann, phD (a,b) Impaired wound Healing.

- Melanie Rodrigues , Nina kasaric , Clark , A. Bonham , and Geoffrey C. Gurtner Wound Healing : A cettular Protective.

- Martin, P & Leibovich, S.J. (2005). Inflammation and wound Healing : The Role of the immune Respose Journal of Investigative Dermato- logy, 125(4), 779 – 788.

- S. Guo and L.A Dipietro factors affecting wound Healing.

- Ana cristina de diveira Gonzalez zilton de Arauja Andrade.

- Holly N. Wilkinson and matthew J. Hardman coound healing : cellular mechanism and pathological outcomes.

- Shailendra singh, Alistair Young, Clare ellen Mc Nought.

- Wayne.k. Stadelmann, MD, Alexander G. Digenis, MD, Gordon R. Jobin, MD Louisville kentucky, physiology and healing dynamics of chronic cutaneous Wound.

- MARJA B. WITTE MD(a) , ADRIAN BARBUL , MD(b) Arginine physiology and it’s implication for wound healing.

- The biology of wound healing: A Comprehensive review in American journal of surgery by D.J. Mcculloch and colleagues.

- P. martin , R. Nunan British Journal of dermatology, Volume 173, issue 2, 1 August 2015, pages 370-378 Cellular & molecular mechanism. Of repair in acute and chronic wound healing.

- Guo, S., & DiPietro, L. A. (2010). "Factors Affecting Wound Healing." Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219-229. doi:10.1177/0022034509357739.

- Pastar, I., et al. (2014). "Wound Healing and Healing Dysfunction." International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 15(11), 21580-21621. doi:10.3390/ijms151121580.

- Wysocki, A. B., & Gil, A. (2015). "Chronic Wound Healing: Mechanisms and Management." Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 72(2), 196-205. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.015.

- Peng – Hui wang(a,b,c) , Ben-Shian Huang(a,b,c) , Huann-cheng Horng(a,b,c), Chang. Ching Yeh(a,b,c) Yi- Jen chen wound healing journal of Chinese medical association 81 (2018)94-101.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. “Wound Repair and Regeneration.” Nature 2008, 453(7193):314-321.

- Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance.” J Cell Sci 2010; 123(Pt 24):4195-4200

- Witte MB, Barbul A. “General Principles of Wound Healing. Surg Clin North Am 1997, 77(3):509-528.

- Eming SA, Hammerschmidt M, Krieg T, et al. “Interrelation of wound healing and inflammation. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127(5):1018-1027

- Wolfe RR. “The underappreciated role of protein in healing. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204(2):233-239

- Omeroglu S, Tuncer I, Tuncer A, et al. “The effects of aging on wound healing.” Ageing Res Rev 2015; 24(P1 A):107-115.

- Frydi J, Tmej A, Svoboda M, et al. “Wound healing in diabetic patients. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2018, 162(2):210-215.

- Leaper D.J. “Infection in wounds: the importance of early recognition.” Wound Repair Regen 2006, 14(4):435-438.

- Nussbaum, S. R., et al. (2018). "Wound Healing: An Overview of Current and Emerging Treatments." Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology, 4(1): 1-10.

- Wiegand, C., et al. (2015). "The role of honey in wound healing." Wound Repair and Regeneration, 23(2): 165-179.

- Kumar, S., & Venkatesh, R. (2020). "The role of topical agents in the management of wounds." International Journal of Surgery, 78: 63-71.

- Jull AB, et al. (2015) "Honey as a topical treatment for wounds." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Falanga V. (2005). "Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. The Lancet.

- Jansen M, et al. (2011). "Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on wound healing: A review. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

- Ahn J, et al. (2008). 'Topical antibiotics in the management of skin and soft tissue infections." Journal of Infection.

- Tice AD, et al. (2004). "Practice guidelines for the management of skin and soft tissue infections." Clinical Infectious Diseases.

- Dahan A, et al. (2012). "Opioids and wound healing Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care.

- Wound Healing Society. (2003). The role of nutrition in wound healing"

- Saha 5, et al. (2020) "Stern cell ther in wound healing: A review Stem Cell Research & Therapy.

Rutuja V. Shelke*

Rutuja V. Shelke*

10.5281/zenodo.14160017

10.5281/zenodo.14160017