Abstract

A syndrome known as fibromyalgia is characterised by widespread, chronic pain in the muscles and skeletal system. For many patients, these symptoms last for years and force them to seek medical attention frequently; for some, fibromyalgia and associated symptoms can be incapacitating. There are still features of this illness that are puzzling. It is understood that the central sensitization phenomenon that underlies fibromyalgia is characterised by neurocircuit dysfunction. This dysfunction involves the perception, transmission, and processing of afferent nociceptive stimuli, with the locomotor system experiencing pain most frequently. The central nervous system's serotonergic and noradrenergic, but not opioidergic, transmission appears to be impaired in fibromyalgia and other associated illnesses. The increased level of pronociceptive neurotransmitters like glutamate and substance P may also be responsible for the increased state of pain transmission. Psychological and behavioural issues can also be at play in some situations. Although the symptoms of fibromyalgia and associated diseases may overlap, a thorough physical examination and careful observation can aid clinicians in making a precise diagnosis.

Keywords

: Fibromyalgia, Central pain syndrome, musculoskeletal pain, Treatment of fibromyalgia, Central Nervous System sensitization

Introduction

Fibromyalgia represents a complex and enigmatic medical condition that challenges contemporary medical understanding, particularly in the realm of chronic pain management. Etymologically, the term itself provides insight into its fundamental nature: 'fibro' referencing fibrous tissue, 'my' signifying muscle, and 'algia' denoting pain. This intricate syndrome manifests as a profound neurological disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain that transcends traditional medical explanations.

The pathophysiological landscape of fibromyalgia remains shrouded in scientific uncertainty. Current research suggests that the syndrome is not fundamentally an inflammatory condition affecting muscles, ligaments, or tendons. Instead, contemporary theories emphasize a sophisticated neurological dysfunction centered on pain regulation mechanisms and central nervous system sensitization. The central nervous system becomes remarkably hypersensitive, creating a perplexing scenario where pain perception becomes distorted, generating sensations of pain even in the absence of apparent physical trauma. Epidemiologically, fibromyalgia exhibits distinct demographic characteristics, predominantly affecting females at a striking ratio of 3-6:1 compared to males. The syndrome's onset spans a considerable age range, typically emerging between 20 and 64 years, indicating its potential to impact a substantial segment of the population. Prevalence estimates suggest that approximately 2-5% of the general population experiences this condition, with incidence rates incrementally increasing with age.

The syndrome's complexity is further underscored by its frequent comorbidities. Patients often simultaneously experience conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome, myofascial pain syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, and notable psychological manifestations like anxiety and depression. This intricate web of associated disorders suggests that fibromyalgia is not merely a localized pain condition but a sophisticated neurological phenomenon with widespread systemic implications.

Diagnostic challenges are inherent in fibromyalgia's presentation. Traditional diagnostic approaches rely heavily on comprehensive medical histories, meticulous physical examinations, and the systematic exclusion of alternative pathological explanations. The American College of Rheumatology's diagnostic criteria, established in 1990, originally emphasized widespread pain duration and specific tender point sensitivity. However, contemporary medical perspectives recognize the limitations of these initial diagnostic frameworks, advocating for more nuanced, holistic assessment methodologies.

The syndrome's impact extends far beyond physical discomfort, profoundly affecting patients' quality of life. Numerous studies have documented significant functional limitations, with substantial percentages of patients experiencing employment disruptions and chronic disability. The persistent nature of

symptoms—including profound fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairments, and widespread pain—creates a comprehensive medical challenge that demands sophisticated, multidimensional treatment approaches. Treatment strategies for fibromyalgia have evolved to embrace a multifaceted approach. Conservative interventions emphasize lifestyle modifications, including structured exercise regimens, sleep hygiene optimization, and stress management techniques. Pharmacological treatments typically involve targeted medication protocols, often incorporating low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsant medications. The ongoing scientific discourse surrounding fibromyalgia underscores the necessity for continued research into its intricate neurological mechanisms. While current understanding highlights central nervous system sensitization as a primary contributor, significant knowledge gaps remain. Future investigations must focus on unraveling the complex interactions between neurological, psychological, and physiological factors that contribute to this enigmatic syndrome.

Ultimately, fibromyalgia represents a profound medical challenge that demands interdisciplinary collaboration, compassionate patient care, and relentless scientific inquiry. As medical understanding continues to evolve, the potential for more targeted, effective interventions grows, offering hope to millions of individuals navigating the complex landscape of chronic pain management [1-5].

Fig.1. Fibromyalgia Symptoms

Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Syndrome

Fibromyalgia (FM) is part of a group of common syndromes characterized by persistent, unexplained chronic pain and fatigue. Key features of FM include enduring widespread pain and multiple tender points found throughout the body upon physical examination. Clinical descriptions of what is now known as FM date back to the mid-1800s, with terms like "neurasthenia" and "muscular rheumatism" originally used. The term "fibrositis" was introduced by Gowers in 1904 and used until the 1970s and 1980s when it became evident that the syndrome's origin lies in the central nervous system (CNS). Pioneering studies by Smythe and Moldofsky highlighted associated sleep pathology, shaping our current understanding of FM as a result of both central and peripheral pain sensitization mechanisms contributing to its defining symptoms [6-8].

Diagnosing Fibromyalgia (FM) involves a comprehensive approach, combining patient history, physical examination, laboratory assessments, and the exclusion of alternative causes for FM-like symptoms. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) established two major diagnostic criteria for adults. The first criterion necessitates a history of widespread pain lasting at least 3 months, while the second requires patients to report tenderness in at least 11 of 18 specified tender points when digitally palpated with approximately 4 kg per unit area of force. The diagnostic relevance of tender points was affirmed in reports from the 1980s, demonstrating their ability to differentiate fibromyalgia from controls [9, 10].

The pain associated with fibromyalgia is often described as a deep, widespread, gnawing, or burning ache, variable in radiance. Pain self-rating may exceed that of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Virtually all patients experience severe fatigue, particularly in the morning despite adequate sleep, worsening by mid-afternoon, and described as physically or emotionally draining. Poor sleep patterns, stiffness, skin tenderness, postexertional pain, irritable bowel syndrome, cognitive disturbance, irritable bladder syndrome, tension or migraine headaches, dizziness, fluid retention, paresthesias, restless legs, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and mood disturbances are additional features of fibromyalgia. The three key features—pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance—are present in almost every fibromyalgia patient [11, 12].The ACR tender point criteria, although accepted for clinical diagnosis, have faced criticism. Some individuals with chronic widespread pain have fewer than the 11 of 18 tender points specified, and critics argue that this requirement may artificially increase the female predominance of fibromyalgia. It has been noted that the ACR criteria focus solely on pain, neglecting other vital symptoms of fibromyalgia, and that an exclusive focus on pain might fail to capture the "essence" of the syndrome [13, 14].

Approximately 10%-11% of the population experiences chronic widespread pain at any given time, with about one-fifth meeting the 11 of 18 tender points specified in the ACR criteria. Chronic regional pain affects 20%-25%. Even defined by the ACR criteria, FM is estimated to affect about 2% of the adult population (18 years and older) in the USA, with a prevalence of 3.4% in women compared to 0.5% in men. It is diagnosed in 5%-6% of adult patients in general medical and family practice clinics and in 10%-20% of adult patients seen by rheumatologists, making it a common diagnosis in office-based rheumatology practices. To differentiate fibromyalgia symptom characteristics from those present in other patients with chronic pain, assessments must be sensitive to differences between FM and other chronic pain states. Up to 80% of fibromyalgia patients also meet criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome, while substantial overlap exists with headaches, temporomandibular disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome. The high comorbidity in fibromyalgia patients and the similarity between cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia and closely related diseases make assessing the effects of treatment on fibromyalgia symptoms challenging. Many fibromyalgia patients endure significant disability and a diminished quality of life. A survey in the mid-1990s indicated that 25.3% of patients received disability payments, with only 25% specifically for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. A smaller cohort study revealed even greater disability, reporting that 31% of patients employed before the onset of fibromyalgia experienced employment loss due to the disease. The disability associated with fibromyalgia remains relatively stable over time. For instance, in a large cohort of 538 patients monitored for 7 years and assessed every 6 months using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), functional disability showed a slight worsening over the study period. Additionally, indicators such as pain, global severity, fatigue, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression were all abnormal at the start of the study (an average of 7.8 years after disease onset) and remained essentially unchanged throughout the research period.

The pain, disability, and other symptoms of fibromyalgia lead to a significantly diminished quality of life for affected individuals. A comparison between women with fibromyalgia and those with various health conditions, including healthy women and individuals with RA, osteoarthritis, permanent ostomies, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or type 1 diabetes, revealed consistently lower scores for those with fibromyalgia across nearly all evaluated domains. A more focused comparison of 44 women with FM and 41 with RA indicated similar levels of disability and negative impacts on quality of life between the two conditions [15, 16].

Pathophysiology Behind Fibromyalgia

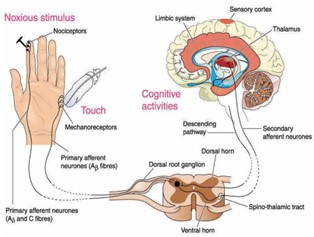

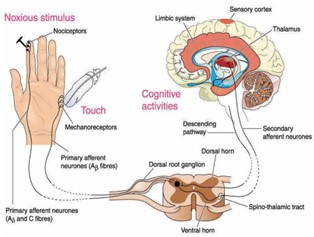

The pathophysiology of fibromyalgia represents a complex neurobiological puzzle that extends far beyond traditional pain mechanisms. At its core, the syndrome appears to stem from a fundamental dysregulation of pain processing within the central nervous system. Researchers have identified a critical phenomenon of central sensitization, where the nervous system becomes hypersensitive to pain stimuli, causing an amplified perception of pain even in the absence of apparent tissue damage. This neurological recalibration involves intricate changes in neurotransmitter systems, particularly the serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways, which play crucial roles in pain modulation and emotional regulation. The neurochemical landscape of fibromyalgia is characterized by significant imbalances in pronociceptive neurotransmitters. Elevated levels of glutamate and substance P contribute to an enhanced state of pain transmission, creating a persistent cycle of heightened pain perception. Simultaneously, the opioidergic system appears compromised, reducing the body's natural pain-dampening mechanisms. This neurochemical disruption is accompanied by alterations in neuroendocrine functioning, particularly involving stress response systems and hormonal regulations that may further exacerbate pain sensitivity. Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies have revealed subtle but significant changes in brain regions responsible for pain processing. Patients with fibromyalgia demonstrate altered functional connectivity and neural activity in areas like the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and thalamus, which are critical for pain perception and emotional interpretation of sensory experiences. These neuroplastic changes suggest that fibromyalgia is not merely a pain disorder but a complex neurological syndrome involving intricate interactions between sensory, emotional, and cognitive processing mechanisms.

Psychological and behavioral factors also play a substantial role in the pathophysiological framework. Chronic stress, anxiety, and depression are frequently associated with fibromyalgia, suggesting bidirectional relationships between neurochemical dysregulation and psychological states. The persistent activation of stress response systems can further perpetuate neuroinflammatory processes and maintain the heightened pain sensitivity characteristic of the syndrome. Genetic predispositions may also contribute to fibromyalgia's pathophysiology, with research indicating potential hereditary components that influence pain processing, neurotransmitter functioning, and stress response mechanisms. The interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers creates a complex etiological landscape that makes fibromyalgia a multifactorial condition challenging to diagnose and treat comprehensively.

This intricate pathophysiological understanding emphasizes fibromyalgia as a sophisticated neurological disorder involving complex interactions between neural, hormonal, psychological, and genetic systems, rather than a simple musculoskeletal pain syndrome. The emerging research underscores the need for holistic, multidimensional approaches to understanding, diagnosing, and managing this challenging condition [17-20].

Fig.2. Tentative Pathophysiology of Fibromyalgia

Susceptibility to FM and Precipitating Factors:

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of fibromyalgia can be difficult. Because there is no suitable laboratory findings which proves that particular individual suffering from fibromyalgia. The diagnosis typically based on medical history, physical exams and in order to their laboratory test.

So, on the basis of medical history, it is often justified that patients complaining of widespread musculoskeletal pain on those areas in their bodies (which mentioned earlier) and they have that pain which occurring at least 3 months. Another one is accompanied by fatigues and sleep disturbances and other associated symptoms like headaches, cognitive disturbances, IBS etc. So again it is observed that the patient with widespread musculoskeletal pain, multisite focal tenderness where they have oftentimes extreme fatigue and it is chronic and persistent and they have sleep disturbances and they have some other associated symptoms as well. Finally all of these occurring and existing for at least 3 months.In case of physical examinations, it is find that widespread tenderness on palpation in the same areas (which mentioned earlier). But it is not observed that any signs of joint swelling or inflammation and laboratory findings of all essential biomarkers (CBC, ESR and CRP) normal in range. So those are the ways of diagnosis fibromyalgia [21-24].

Treatment

The comprehensive management of fibromyalgia requires a multifaceted therapeutic approach that addresses the complex nature of this chronic pain syndrome. Initial treatment strategies focus on non-pharmacological interventions designed to improve overall patient quality of life and manage symptoms holistically. Patients are typically first advised to implement lifestyle modifications that can significantly impact their symptom management. Sleep hygiene emerges as a critical component of this approach, with healthcare providers recommending consistent sleep schedules, creating a conducive sleep environment, and minimizing potential sleep disruptors. Dietary and lifestyle modifications play a crucial role in symptom management. Patients are strongly encouraged to reduce caffeine intake, particularly during evening hours, as caffeine can exacerbate sleep disturbances and potentially intensify pain sensitivity. Nutritional counseling often accompanies these recommendations, with an emphasis on maintaining a balanced diet that supports overall health and potentially mitigates inflammatory responses.

Exercise emerges as a cornerstone of non-pharmacological treatment, with a carefully structured approach tailored to individual patient capabilities. Aerobic exercises are particularly recommended, combining cardiovascular conditioning with gentle strengthening and stretching techniques. These exercise protocols are designed to improve physical function, reduce pain perception, and enhance overall muscular endurance. Physical therapists and healthcare providers typically develop personalized exercise plans that gradually increase in intensity, taking into account the patient's pain threshold and physical limitations. When conservative therapies prove insufficient, the treatment paradigm shifts towards pharmacological interventions. The medication approach follows a strategic, stepwise methodology. Initially, clinicians conduct a comprehensive assessment to identify any underlying conditions that might be contributing to or exacerbating fibromyalgia symptoms. This careful evaluation ensures a targeted treatment approach that addresses potential comorbidities.

Initial monotherapy typically involves tricyclic antidepressants, with Amitriptyline emerging as the primary first-line treatment. This medication approach targets the complex neurochemical imbalances associated with fibromyalgia, addressing both pain perception and potential mood-related symptoms. Alternatively, Cyclobenzaprine presents itself as a viable option, particularly for patients with significant muscle-related symptoms. Despite being a muscle relaxant with a chemical structure similar to Amitriptyline, it offers a complementary approach to symptom management. When monotherapy fails to provide adequate symptom relief, clinicians progress to combination therapy strategies. These advanced treatment protocols often involve carefully balanced medication combinations designed to target multiple symptom dimensions. One approach combines a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) such as Fluoxetine in the morning, paired with a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant like Amitriptyline at night. This strategy aims to optimize neurotransmitter regulation and provide round-the-clock symptom management.

Another sophisticated combination approach involves a low-dose SNRI like Duloxetine combined with a low-dose anticonvulsant such as Pregabalin. This combination targets both neurochemical modulation and pain signal processing, offering a more comprehensive treatment strategy for patients with persistent and complex fibromyalgia symptoms. It is crucial to recognize that treatment is inherently individualized, requiring close collaboration between healthcare providers and patients. Regular follow-ups, careful medication monitoring, and a willingness to adjust treatment protocols are essential for optimizing patient outcomes. The goal extends beyond mere symptom suppression, focusing instead on improving overall functional capacity and quality of life for individuals navigating the challenges of fibromyalgia [25-30].

CONCLUSION

Fibromyalgia represents a complex and enigmatic neurological disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, profound neurophysiological dysregulation, and multisystemic manifestations predominantly affecting women. This intricate syndrome transcends traditional pain paradigms, encompassing a sophisticated interplay between neurological, psychological, and physiological mechanisms that challenge contemporary medical understanding. Central nervous system sensitization emerges as a pivotal mechanism, fundamentally altering sensory processing and pain perception mechanisms through intricate neurotransmitter and neurohormonal modifications. The neurobiological landscape of fibromyalgia reveals a sophisticated disruption of pain modulation circuits, where the central nervous system becomes hypersensitive to stimuli, generating pain experiences disproportionate to external physical triggers. Women, representing approximately 80% of diagnosed cases, experience a more profound neurological sensitivity, suggesting potential hormonal and genetic predispositions that render their neural networks more susceptible to sensitization phenomena. This gender-specific vulnerability underscores the complexity of understanding fibromyalgia's pathogenesis beyond simplistic biomechanical explanations.

Comorbid conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular dysfunction, and chronic fatigue syndrome further illuminate the syndrome's multidimensional nature. These interconnected disorders suggest a broader neurological dysfunction that extends beyond localized pain manifestations, indicating a comprehensive dysregulation of neural processing and emotional regulation mechanisms. The intricate relationship between these conditions hints at shared underlying neurological and neuroendocrine pathways that potentially contribute to widespread pain experiences. Treatment strategies have evolved from purely symptomatic management to a more holistic, multidisciplinary approach. Low-dose tricyclic medications like amitriptyline and cyclobenzaprine represent pharmacological interventions targeting neurochemical imbalances. Simultaneously, non-pharmacological approaches such as cardiovascular exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and patient education demonstrate significant potential in modulating pain perception and improving overall quality of life. These comprehensive treatment modalities acknowledge fibromyalgia's complex neurobiological underpinnings, emphasizing rehabilitation and adaptive strategies. The syndrome's neurological complexity challenges traditional pain management paradigms, necessitating a nuanced understanding of central nervous system sensitization. Emerging research suggests that fibromyalgia represents not merely a pain disorder but a sophisticated neurological syndrome involving intricate interactions between sensory processing, emotional regulation, and physiological responsiveness. This perspective shifts medical discourse from viewing fibromyalgia as a localized pain condition to recognizing it as a comprehensive neurological phenomenon with widespread systemic implications.

As medical knowledge continues to advance, fibromyalgia research promises to unravel increasingly sophisticated insights into neural plasticity, pain perception, and the intricate relationships between neurological, psychological, and physiological domains. The ongoing exploration of this syndrome represents a critical frontier in understanding human neural complexity, offering potential breakthroughs in comprehending and managing chronic pain experiences that extend far beyond traditional biomedical frameworks.

REFERENCE

- Mease P, Arnold LM, Bennett R, Boonen A, Buskila D, Carville S, Chappell A, Choy E, Clauw D, Dadabhoy D, Gendreau M. Fibromyalgia syndrome. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2007 Jun 1;34(6):1415-25.

- Bellato E, Marini E, Castoldi F, Barbasetti N, Mattei L, Bonasia DE, Blonna D. Fibromyalgia syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Pain research and treatment. 2012;2012.

- Mease P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatment. The Journal of Rheumatology Supplement. 2005 Aug 1;75:6-21.

- Turhano?lu AD, Yilmaz ?, Kaya S, Dursun M, Kararmaz A, Saka G. The epidemiological aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome in adults living in turkey: a population based study. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 2008 Jan 1;16(3):141-7.

- Garip Y, Güler T, Tuncer ÖB, Sinay ÖN. Type d personality is associated with disease severity and poor quality of life in turkish patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: A cross- sectional study. Archives of Rheumatology. 2020 Mar;35(1):13.

- Cassisi G, Sarzi-Puttini P, Alciati A, Casale R, Bazzichi L, Carignola R, Gracely RH, Salaffi F, Marinangeli F, Torta R, Giamberardino MA. Symptoms and signs in fibromyalgia syndrome. Reumatismo. 2008;60(s1):15-24.

- Russell IJ, Larson AA. Neurophysiopathogenesis of fibromyalgia syndrome: a unified hypothesis. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 2009 May 1;35(2):421-35.

- Simms RW. Is there muscle pathology in fibromyalgia syndrome?. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 1996 May 1;22(2):245-66.

- Häuser W, Sarzi-Puttini P, Fitzcharles MA. Fibromyalgia syndrome: under-, over-and misdiagnosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 1;37(Suppl 116):90-7.

- Yunus MB, Kalyan-Raman UP, Kalyan-Raman K, Masi AT. Pathologic changes in muscle in primary fibromyalgia syndrome. The American journal of medicine. 1986 Sep 29;81(3):38-42.

- Binkiewicz-Gli?ska A, Baku?a S, Tomczak H, Landowski J, Ruckemann-Dziurdzi?ska K, Zaborowska-Sapeta K, Kiebzak W. Fibromyalgia Syndrome-a multidisciplinary approach. Psychiatr Pol. 2015 Jan 1;49(4):801-10.

- Buchwald D. Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: similarities and differences. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 1996 May 1;22(2):219-43.

- Van Houdenhove B, Kempke S, Luyten P. Psychiatric aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Current psychiatry reports. 2010 Jun;12(3):208-14.

- Bohn D, Bernardy K, Wolfe F, Häuser W. The association among childhood maltreatment, somatic symptom intensity, depression, and somatoform dissociative symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a single-center cohort study. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2013 May 1;14(3):342-58.

- Jurado-Priego, L. N., Cueto-Ureña, C., Ramírez-Expósito, M. J., & Martínez-Martos, J. M. (2024). Fibromyalgia: A Review of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Multidisciplinary Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines, 12(7), 1543.

- Silva, F. M., Pacheco-Barrios, K., & Fregni, F. (2024). Disruptive compensatory mechanisms in fibromyalgia syndrome and their association with pharmacological agents. Experimental Brain Research, 1-14.

- Jurado-Priego, L. N., Cueto-Ureña, C., Ramírez-Expósito, M. J., & Martínez-Martos, J. M. (2024). Fibromyalgia: A Review of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Multidisciplinary Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines, 12(7), 1543.

- Bruti, G., & Foggetti, P. (2024). Insecure Attachment, Oxytocinergic System and C-Tactile Fibers: An Integrative and Translational Pathophysiological Model of Fibromyalgia and Central Sensitivity Syndromes. Biomedicines, 12(8), 1744.

- Specktor, P., Hadar, D., & Cohen, H. (2024). Glucocorticoid treatment during COVID-19 infection: does it affect the incidence of long COVID?. Inflammopharmacology, 1-9.

- Karacaoglu, C., Ersoy, S., Pala, E., & Engin, V. S. (2024). Evaluation of the effectiveness of wet cupping therapy in fibromyalgia patients: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary Medicine Research, 31(1), 10-19.

- Venerito, V., & Iannone, F. (2024). Large language model-driven sentiment analysis for facilitating fibromyalgia diagnosis. RMD open, 10(2), e004367.

- Agarwal, A., Emary, P. C., Gallo, L., Oparin, Y., Shin, S. H., Fitzcharles, M. A., ... & Busse, J. W. (2024). Physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Medicine, 103(31), e39109.

- Fernandes-Magalhaes, R., Carpio, A., Ferrera, D., Peláez, I., De Lahoz, M. E., Van Ryckeghem, D., ... & Mercado, F. (2024). Neural mechanisms underlying attentional bias modification in fibromyalgia patients: a double-blind ERP study. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 274(5), 1197-1213.

- Taub, R., Agmon-Levin, N., Frumer, L., Samuel-Magal, I., Glick, I., & Horesh, D. (2024). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for fibromyalgia patients: The role of pain cognitions as mechanisms of change. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 56, 101860.

- Pacheco-Barrios, K., Teixeira, P. E., Martinez-Magallanes, D., Neto, M. S., Pichardo, E. A., Camargo, L., ... & Fregni, F. (2024). Brain compensatory mechanisms in depression and memory complaints in fibromyalgia: the role of theta oscillatory activity. Pain Medicine, pnae030.

- Pacheco-Barrios, K., Teixeira, P. E., Martinez-Magallanes, D., Neto, M. S., Pichardo, E. A., Camargo, L., ... & Fregni, F. (2024). Brain compensatory mechanisms in depression and memory complaints in fibromyalgia: the role of theta oscillatory activity. Pain Medicine, pnae030.

- Nimbi, F. M., Renzi, A., Limoncin, E., Bongiovanni, S. F., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Galli, F. (2024). Central sensitivity in fibromyalgia: testing a model to explain the role of psychological factors on functioning and quality of life. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 42(6), 1187- 1197.

- Badaeva, A., Danilov, A., Kosareva, A., Lepshina, M., Novikov, V., Vorobyeva, Y., & Danilov, A. (2024). Neuronutritional approach to fibromyalgia management: A narrative review. Pain and therapy, 13(5), 1047-1061.

- Climent-Sanz, C., Hamilton, K. R., Martínez-Navarro, O., Briones-Vozmediano, E., Gracia-Lasheras, M., Fernández-Lago, H., ... & Finan, P. H. (2024). Fibromyalgia pain management effectiveness from the patient perspective: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Disability and rehabilitation, 46(20), 4595-4610.

- Rubio-Zarapuz, A., Apolo-Arenas, M. D., Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., Parraca, J. A., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2024). Comparative efficacy of neuromodulation and structured exercise program on pain and muscle oxygenation in fibromyalgia patients: a randomized crossover study. Frontiers in Physiology, 15, 1414100.

Manav Kumar*

Manav Kumar*

Ankita Singh

Ankita Singh

Mahesh Kumar Yadav

Mahesh Kumar Yadav

Kajal Kumari

Kajal Kumari

Sapna Kumari

Sapna Kumari

10.5281/zenodo.14513089

10.5281/zenodo.14513089